Location: Historic American Sheet Music Collection, Duke University, Durham, North Carolina

Title of Song: “Good Enough!”

Composer: Rollin Howard

Engraver: Clayton’s

Lithographer: Chicago Lithographing

Publisher: Lyon & Healy

Year & Place: 1871, Chicago, Illinois

Collection/Call Number/Copies: Music B-498

Historic American Sheet Music Item #: b0498

Basic Description

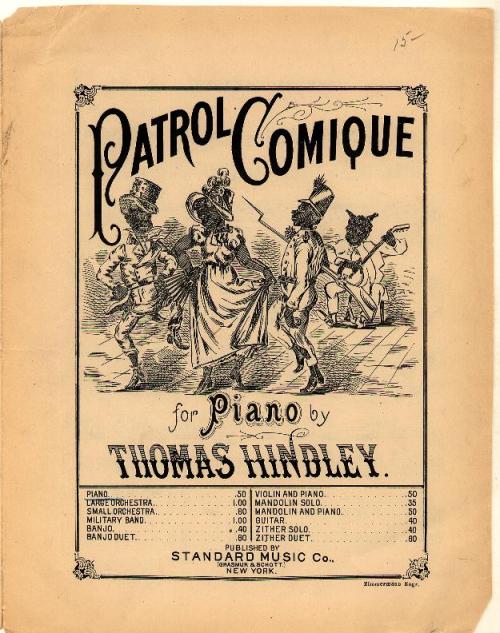

A dancing, high-kicking couple are shown in an interior space. Upon closer inspection it appears as if the woman is wearing a nineteenth-century styled slip and petticoats, which is further suggested by the hoop-skirt frame sitting on the table behind her, and in the shelving and racks in the room holding linen, socks, and possibly other forms of apparel. Both the man and the woman wear big, black brogans and garishly striped stockings.

Personal Description

The abandonment which is expressed in this couple’s dance moves, along with her undressed state, his clown-like outfit, and their shared gnome-like, diabolical features, all conveyed a kind of idiocy and madness surrounding African Americans that, in the post-Reconstruction era, contributed towards the complete dismantling of what few legal rights and social courtesies black still had circa 1871.

Reality Check

John Jones (1816-1879) & Mary Richardson Jones (1819-1910)

John Jones – tailor, writer, and politician – was born in 1816 in Green City, North Carolina to a German father and an African American mother. Born free, he taught himself to read and write, started his own tailoring business, and eventually became one of the wealthiest African Americans in the antebellum United States.

While working as a tailor in Memphis, Tennessee in 1841, John Jones met Mary Jane Richardson, the daughter of a free African American blacksmith. Although the Richardson family shortly thereafter moved to Alton, Illinois, Jones remained in Memphis for three years to complete the requirements of his apprenticeship. In 1844 Jones moved to Alton and married Mary Jane Richardson. Although they were free, both John and Mary obtained certificates of freedom, posted a $1,000 bond in Madison County, and gained the privileges of traveling and living in the state.

After moving to Chicago in 1845, the highly skilled tailor soon had a thriving enterprise, catering to many of Chicago’s elites. By 1860 Jones’s business was one of the city’s oldest and most financially solvent, having accumulated between $85,000 and $100,000. The great Chicago fire of 1871 affected his wealth, yet he was left with enough money to be called one of the country’s wealthiest African Americans and Chicago’s undisputed black leader.

Jones used his house and his office, both located on Dearborn Street, as stops on the Underground Railroad through Chicago. His home was known as a meeting place for local and national abolitionist leaders including Frederick Douglass and John Brown. He also authored a number of influential anti-slavery pamphlets. Mary Richardson Jones was also a suffragette, and leaders in the suffrage movement such as Susan B. Anthony stayed in the Jones’ home when visiting Chicago.

Although a dedicated abolitionist, John Jones also actively campaigned against racial discrimination as expressed in the Black Laws of Illinois. Jones dedicated a considerable amount of his wealth to overturn Illinois laws that denied voting rights to black men and banned them from testifying in court. His efforts were successful in 1865 when the Illinois Legislature repealed the Black Laws restricting civil rights. Five years later, in 1870, after ratification of the 15th Amendment, Jones and other Illinois black men also voted for the first time. In 1871, in the aftermath of the Great Chicago Fire, Jones was elected to the Cook County Commission on the Union Fire Proof ticket, becoming the first African American officeholder in the state’s history. While holding this post, he helped enact the law that abolished segregated schools.

Reelected to a full three-year term in 1872, Jones was defeated in his 1875 reelection bid. John Jones died on May 31, 1879, and was buried at Graceland Cemetery in Cook County, Illinois. Mary Richardson Jones died in 1910, and is also buried at Graceland Cemetery.