Location: Historic American Sheet Music Collection, Duke University, Durham, North Carolina

Title of Song: My Home in Alabam’

Composer: Putnam, James S.

Publisher: John F. Perry

Year & Date: 1881, Boston, Massachusetts

Collection/Call Number/Copies: Music# B-666

Historic American Sheet Music Item #: b0666

Basic Description

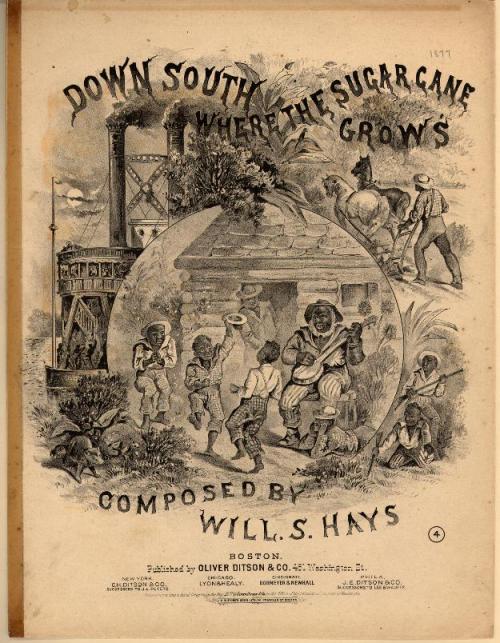

A man sits on a wooden chair in a sparse garret bedroom with a banjo on his lap and his head in his hand. He stares at the viewer with a distant, troubled look, in a pose like Auguste Rodin’s “The Thinker.” The town-like setting in the window contrasts with the plantation scene above— a dream space corralled by a dense frame of cloud-like circles. The cracks and exposed bricks in the wall, along with the jagged hemlines of the man’s pant legs set depressing tone. Rather than being integrated with the picture, the title text is set in the white space around the image. Two title options, “My Dear Savannah Home,” and “My Home in Alabam” are listed in sober typeface.

Personal Description

Each title option can lead to a different and contradictory interpretation of the image. Interestingly, this pamphlet includes two song sheet covers for other “plantation melodies” printed by the same publisher. This imagery makes light of the plantation experience, showing caricatured African Americans dancing or filling pails with berries. Like the song illustrated on the main cover, these songs also have two titles each that contrast oddly with each other. “De Huckleberry Picnic” implies a recreational activity at one’s own free will but “Since I Saw de Cotton Grow” suggests the forced labor of slavery or the exploitation of sharecropping. “My Dear Savannah Home” implies that the seated man is nostalgic for plantation life. But “My Home in Alabam” is vague, allowing the plantation memory invading the scene to be interpreted not as a cherished dream but rather an oppressive nightmare.

Reality Check

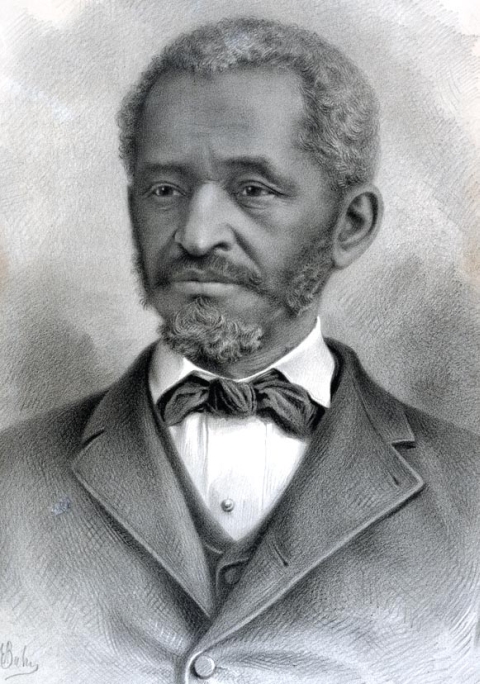

Edward Alexander Bouchet

(1852-1918)

Edward Alexander Bouchet was an educator and scientist who was born in New Haven Connecticut. His family was a member of the Temple Street Congregational Church, a stopping point for fugitive slaves along the Underground Railroad.

In 1868, Bouchet was accepted into Hopkins Grammar School, a private institution that prepared young men for the classical and scientific departments at Yale College. He graduated first in his class at Hopkins and graduated from Yale in 1874, ranking sixth in his class. In 1876, he completed a dissertation on geometrical optics, becoming the first African American to earn a PhD from an American University and the sixth American of any race to earn a PhD in Physics.

Bouchet moved to Philadelphia in 1876 to teach at the Institute for Colored Youth, the city’s only high school for African American students. Bouchet gave public lectures to his community in Philadelphia on scientific topics and was a member of the Franklin Institute, a foundation for the promotion of the mechanic arts, chartered in 1824.

In 1908, he became principal of Lincoln High School in Gallipolis, Ohio, where he remained until 1913, when an attack of arteriosclerosis compelled him to resign and return to New Haven. He died in his boyhood home in 1916.

(Source: African American Lives, edited by Henry Louis Gates, Jr. and Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham, Oxford University Press, 2004.