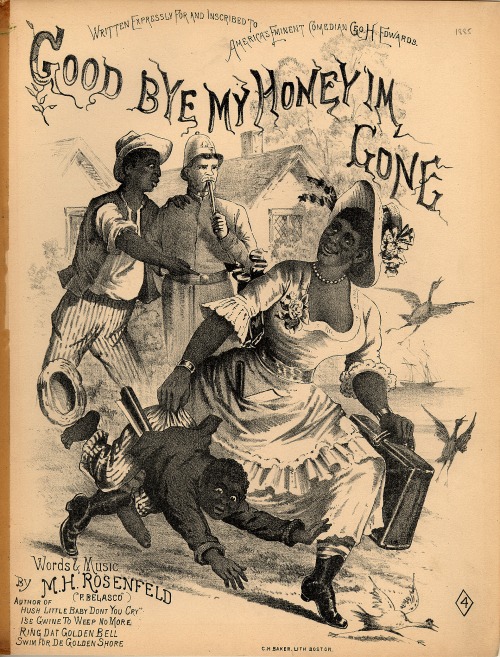

Location: Historic American Sheet Music Collection, Duke University, Durham, North Carolina

Title of Song: “Good Bye My Honey I’m Gone”

Composer: M.H. Rosenfeld

Lithographer: C.H. Baker

Publisher: W.A. Evans

Year & Place: 1885, Boston, Massachusetts

Collection/Call Number/Copies: Music B-490

Historic American Sheet Music Item #: b0490

Basic Description

This lithograph depicts a well-dressed African American woman, valise and African American boy in tow, boldly walking away from two men: one white, in a policeman’s uniform and holding a billy club to his mouth, and the other black, leaning on the officer and pointing in the woman’s direction. To the immediate right of the woman three chickens fly away and, in the distance, a sailing ship exits right. Behind the men are the traceries of two, cottage-like buildings. Gigantic shaving razors are noticeable in the dress and pants’ pockets of the woman and boy, respectively.

Personal Description

Despite the peripheral chaos (i.e., the scattering chickens and expressions of alarm or puzzlement on the men’s and boy’s faces) and the embedded threats of violence (i.e., the razors), there’s a strange calm pervading this image that’s largely located in the fleeing woman. Is it her pleasant smile, her shapely figure and full bosom, or her Herculean arms and corporeal confidence that assuage what is clearly a scene of domestic dissolution? Her floral corsages, lightning-like ribbons and ruffles, and leather lace-ups sartorially empower her, so one wonders why the artist felt the additional need to fall back on the razor-toting Negro stereotype?

Reality Check

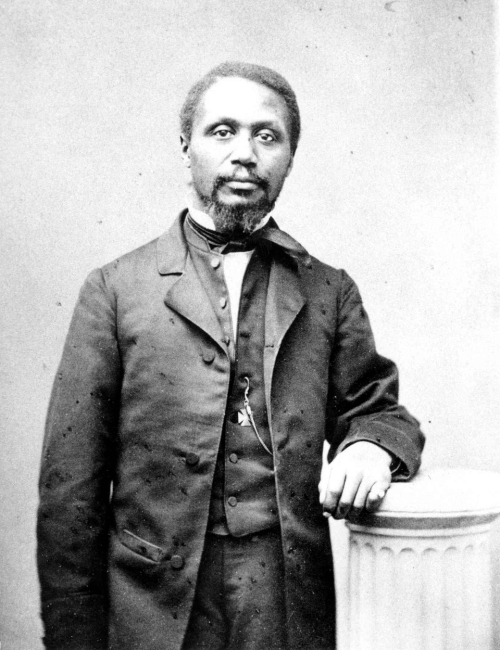

Mary Eliza Mahoney (1845-1926)

Mary Eliza Mahoney, America’s first black graduate nurse, was born in Dorchester, Massachusetts on May 7, 1845. The eldest of three siblings, Mahoney attended the Phillips Street School in Boston.

At the age of twenty, Mary Mahoney began working as a nurse. Supplementing her low income as an untrained, practical nurse, Mahoney took on janitorial duties at the New England Hospital for Women and Children: a state-of-the-art medical facility run solely by female physicians.

In 1878, Mary Mahoney was accepted into the New England Hospital’s graduate nursing program. During her training, Mahoney participated in mandatory sixteen-hour-per-day ward duty, where she oversaw the well-being of six patients at a time. Days not requiring ward duty involved attending day-long lectures while simultaneously devoting time to her studies. Completing the rigorous sixteen-month program, Mahoney was among the three graduates out of the forty students who began the program and the only African American awarded a diploma.

Mary Mahoney worked as a nurse for the next four decades. During her forty-year career she attracted a number of private clients who were among to most prominent Boston families. A deeply religious person, the diminutive five-foot tall, ninety-pound Mahoney devoted herself to private nursing due to the rampant discrimination against black women in public nursing at the time.

Mary Mahoney was widely recognized within her field as a pioneer who opened the door of opportunity for many black women interested in the nursing profession. When the National Association of Colored Graduate Nurses (NACGN) was organized in New York in 1908, Mahoney was asked to give the welcoming address. Following her speech at the 1909 NACGN Convention at Boston, Mahoney was made a lifetime member, exempted from dues, and elected chaplain. Admitted to New England Hospital for care on December 7, 1925, Mahoney succumbed to breast cancer on January 4, 1926 at the age of eighty-one.