Location: Historic American Sheet Music Collection, Duke University, Durham, North Carolina

Title of Song: “Shew Fly!”

Composer: George Thorne & Rollin Howard

Engraver: J. Frank Giles

Publisher: White, Smith & Perry

Year & Place: 1869, Boston, Massachusetts

Collection/Call Number/Copies: Music B-409

Historic American Sheet Music Item #: b0409

Basic Description

This engraving features a solitary male figure, physically gesturing in such a way as to suggest his effort to escape a large, wasp-like insect to the left. A word balloon with the expression “SHOO FLY” issues from the man’s mouth. His big-collared shirt, long-tailed jacket, and striped/patched trousers recall the clothing typically worn by nineteenth-century minstrels.

Personal Description

Although the artist for this cover is not as technically polished as several others in this blog, his attempt at a persuasive African American depiction is laudable. However, like so many of the black figures typically represented on covers, this one also emphasizes the body-in-motion, with angled limbs and twisted torsos carrying their own subliminal messages and allusions.

Reality Check

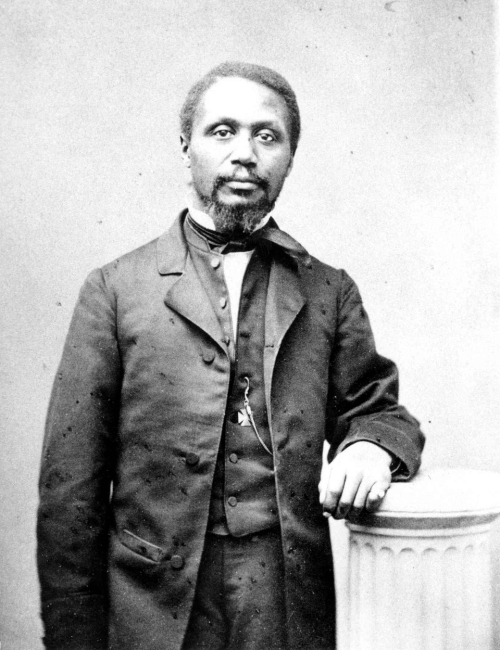

Robert Morris (1823-1882)

Robert Morris became one of the first black lawyers in United States after being admitted to the Massachusetts bar in 1847. Morris was born in Salem, Massachusetts on June 8, 1823. At an early age, Morris had some formal education at Master Dodge’s School in Salem. With the agreement of his family, he became the student of Ellis Gray Loring, a well known abolitionist and lawyer. By the early 1850s, Robert Morris was appointed a justice of the peace and was admitted to practice before U.S. district courts. He occasionally served as a magistrate in courts in Boston and nearby Chelsea, Massachusetts.

Vehemently opposed to slavery, he worked with William Lloyd Garrison, Ellis Loring and Wendell Philips and others to oppose the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. In 1851 Morris, with the help of Lewis Hayden, managed to remove from the courthouse a newly arrested fugitive slave Shadrack and helped him to get to Canada and freedom. Arrests were made but Morris and the others were acquitted of the charges.

With the onset of the Civil War, Morris welcomed President Abraham Lincoln’s call for volunteers but objected to the enlistment of African Americans unless they received fair and equal treatment and were offered positions as officers. He helped in the recruitment of the 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment, the first officially sanctioned African American unit in the U.S. Army but he continued to speak out against discrimination against them and other black soldiers. Robert Morris died in Boston on December 12, 1882.