Location: Historic American Sheet Music Collection, Duke University, Durham, North Carolina

Title of Song: South Car’lina tickle : Cake walk

Composer: Geibel, Adam

Publisher: Theodore Presser

Year & Date: 1898, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Collection/Call Number/Copies: Music # B-376

Historic American Sheet Music Item #: b0376

Basic Description

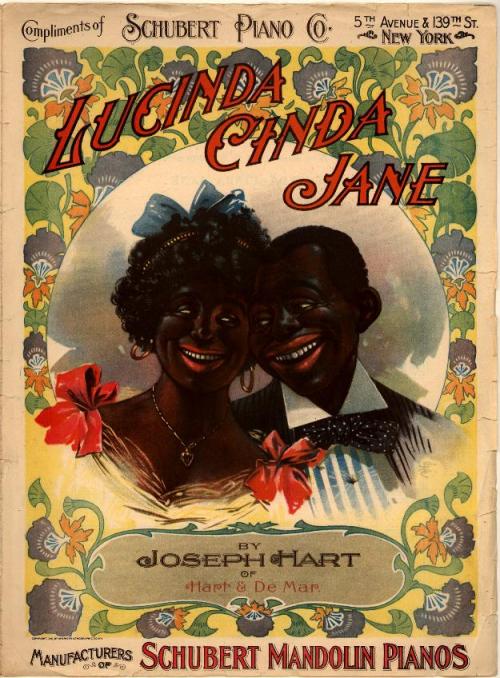

A tall, lanky man in a three-piece suit and a woman in a blouse with puffed sleeves and a long patterned skirt “strut their stuff” with their heads tilted upward. The man holds his right hand up daintily, showing off a glimmering jewel on his pinky finger. The luminosity of the jewel matches the gleaming button or brooch at the center of his ruffled shirt. With his head slightly raised and a smile on his face, he seems proud of his appearance. His yellow-dappled bow-tie and the poufy flower on his lapel nearly rival his head in size. Something that appears to be a medal dangles from his waist and his coat tails flare out jauntily. The woman’s skirt is patterned with what appear to be gourds, and her elaborately-clothed figure casts a dark shadow on the ground. She too holds out her right hand, drawing attention to a ring on her finger, but her attention seems to be caught by the large flower in her left hand.

Personal Description

The self-importance of the couple seems to be a theme in this image, emphasized by the man’s jewels and the almost haughty posture of both figures. However, the presence of three large flowers and the gourd-like design on the woman’s skirt seem to water down or distract from these overt connotations of extravagance and material wealth, almost giving the figures a slightly folksy quality. By 1898, the year this song sheet was published, the cakewalk as a couples dance had become popular in ballrooms and also as a stage act. Couples stepped high to a tune, while judges eliminated them one by one, presenting the best pair with a cake. Couples were judged on their inventiveness, elegance and grace, so the exaggerated poise and costume of the two figures in this image may be a highly exaggerated and caricatured interpretation of the qualities of the dance itself. This could be an ironic reversal of the original meaning of the cakewalk if the theory that it originated among slaves as a satire of white ballroom culture is true.

Reality Check

Gertrude Bustill Mossell (1855-1948) and Nathan Francis Mossell

Gertrude Bustill Mossell was a journalist, author, and member of the women’s suffrage movement. She was born in Philadelphia to a prominent African American family. After graduating from the Robert Vaux Grammar School, she taught school for seven years. In 1893 she married a leading Philadelphia physician, Nathan Frances Mossell. They married in 1893 and had four children together. The marriage ended her career as a teacher since married women were not allowed to teach. In 1894 she published the first of her books, The Work of the Afro-American Woman, a collection of essays and poems illustrating the contemporary work of black women. The book chronicles the achievements of thousands of African American women in different fields.

Bustill was also a journalist, and her articles on political and social issues were published in a number of periodicals including the AME Church Review, the Philadelphia Echo, the Indianapolis Freeman, the Franklin Rankin Institute, and Our Women and Children. Bustill edited the New York Freeman, the Indianapolis World, and the New York Age. In Philadelphia, she wrote syndicated columns in the Echo, the Philadelphia Times, the Independent and the Press Republican. Mossell also assisted in editing the Lincoln Alumni magazine, a journal of the Lincoln University, a prestigious institution for educating black men, such as Bustill’s husband, Nathan Mossell.

Because most hospitals in Philadelphia refused care to black patients, Bustill and her husband raised funds to open the Frederick Douglass Memorial Hospital and Training School. The hospital opened in 1895 with an academic program to help black women become nurses.

Bustill’s husband, Nathan Francis Mossell was a prominent Philadelphia physician born in Canada. After graduating from Lincoln University in Pennsylvania, Mossell entered the University of Pennsylvania Medical School and became the first African-American physician to be elected to the Philadelphia County Medical Society. Dr. Mossell served as superintendent and medical director of the Douglass Memorial Hospital for 47 years. He was a founder of the Philadelphia branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored people and co-founder of the Philadelphia Academy of Medicine and Allied Sciences. He died in 1946. His wife Gertrude died two years later, in 1948.

(Sources: http://www.archives.upenn.edu/people/1800s/mossell_nathan_f.html, New York Times, Dr. Nathan F. Mossell, Oldest Active Negro Physician, Uncle of Paul Robeson, Was 90, October 29, 1946)