Contraband Schottisches

Location: Historic American Sheet Music Collection, Duke University (Durham, North Carolina)

Title of Song: Contraband schottische

Composer: Winner, Septimus

Publisher: Oliver Ditson: Lee & Walker

Year & Place: 1861; Boston, Massachusetts

Collection/Call Number/Copies: Music B-1016

Historic American Sheet Music Item #: hasm.b1016

Basic Description

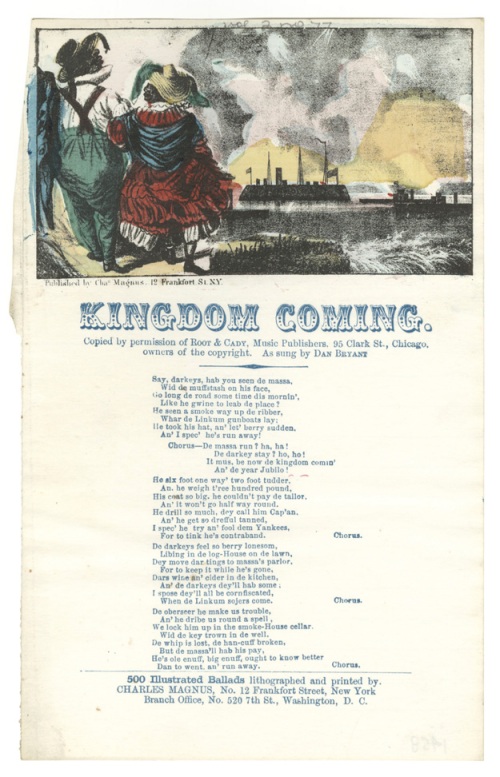

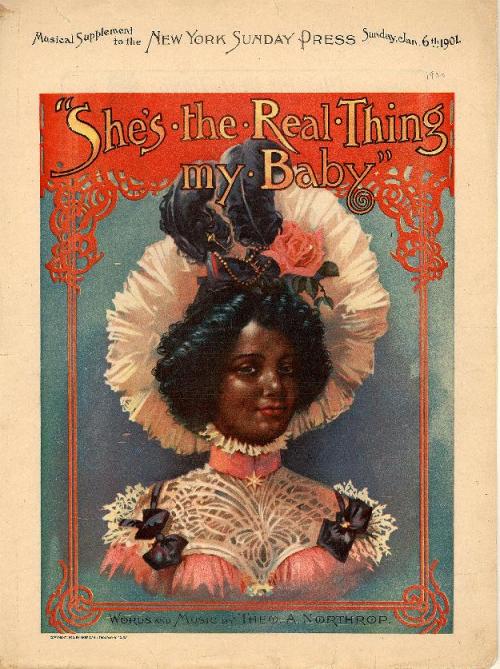

This sheet music’s cover shows its viewer one moment from a longer narrative involving five characters. A white male stands with his fist raised on two steps at the very top of the composition. With a stern countenance, he wears a collared shirt as well as a bowtie, vest and sports jacket. In his right hand he grasps a cane. Below him in a pictorial space separated horizontally by a set of stairs are four black boys. The child in the upper-right hand section of the pictorial space has turned his head to look back at the older man in the midst of running. The other three seem to have stumbled and fallen over on to the ground. The artist here has outfitted all four boys in the same attire which includes a billowy shirt and knickers. While some have no shoes, other boys are in various stages of ‘shoelessness’. The children, while in general disarray, maintain a jovial disposition as evidenced by the slight smiles of those in the foreground.

Personal Description

The composition, body language and written language of this image suggest ambiguity. While the comportment of the black bodies suggests that they are in trouble, having transgressed some unwritten rule, the term contraband that makes up part of the title could mean that they are the trouble. The term contraband during this period referred to escaped slaves who fled from the South. The lack of specific spatial markers disables the viewer from being certain. Still, the positions of their bodies remaind curious. The child in the upper-left portion of the space is practically upside down. Similarly, the boy in the very front sits with his legs splayed open and the child in back of him lies on the ground horizontally. And the boy who turns his head around seems to be suspended in mid-air. The import of these observation is elucidated when they are compared with the only body that stands firmly, vertically upright, that of the older white male. In both analytical contexts, his is a body that polices all of the others.

Reality Check

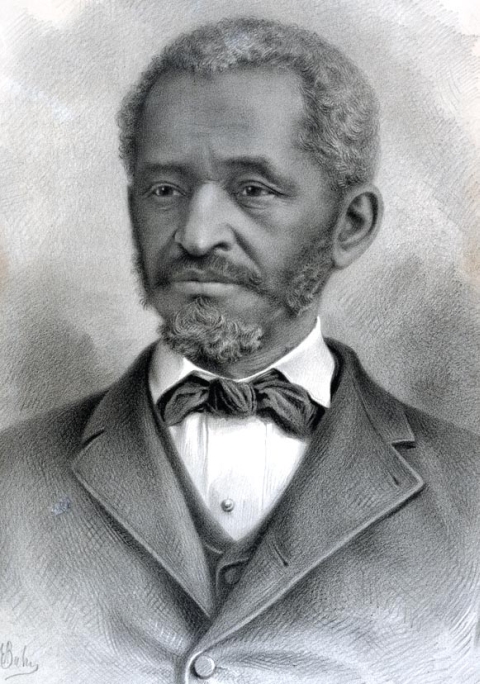

John J. Smith

Born free in Richmond, Virginia, on November 2, 1820, John J. Smith moved to Boston at the age of twenty-eight. With an adventurous and pioneering spirit, Smith went West for the 1849 California Gold Rush but returned to Boston no richer than when he left. At this time he became a barber and set up a shop on the corner of Howard and Bulfinch Streets. His shop was a center for abolitionist activity and a rendezvous point for fugitive slaves. When abolitionist Senator Charles Sumner was not at his home or office, he was usually found at Smith’s shop.

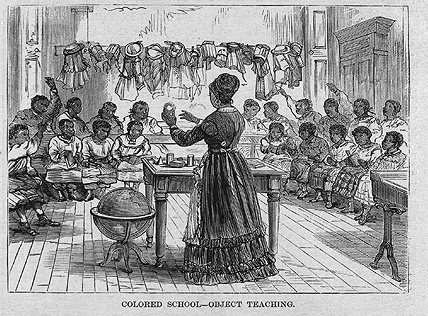

Smith, his wife Georgiana, and other leaders such as Benjamin F. Roberts worked in the 1840s and 1850s in the fight for equal school rights. Boston’s public schools were integrated in 1855 and Smith’s daughter Elizabeth, in the early 1870s, became the first person of African descent to teach in Boston’s integrated schools. John Smith also worked to fight slavery and he was one of the men who played a key role in the rescue of the self-emancipated slave Shadrach Minkins from federal custody in 1851.

During the Civil War, Smith stationed himself in Washington, D.C., as a recruiting officer for the all-black 5th Cavalry. After the war, Smith was elected to the Massachusetts House of Representatives in 1868, 1869 and 1872. In 1878, the year he moved to 86 Pinckney Street, he was appointed to the Boston Common Council. John J. Smith lived at this residence until 1893. He died on November 4, 1906.

(Source: Museum of African American History, Boston and Nantucket, http://www.afroammuseum.org/exhibits.htm; http://www.nps.gov/boaf/historyculture/john-j-smith-house.htm)